Before he left for Tel Aviv, Israel, Jewish real estate developer Joseph Goldberger was taught a painful lesson by the master of looting hive.

By the time Githunguri died last week, the story of how he messed up planned housing in Nairobi’s Tena and Donholm estates had

largely been forgotten.

But it is a story well known in the circles of “old money” – after

Goldberger sought justice over a Sh50 million swindle, the case was

heard on camera.

Apparently, Githunguri, unwilling to have the scandal publicised,

told the judge that some of the evidence he was about to give

touched on “national security”.

It was a lie, but Justice Simpson only realised later that Githunguri

had duped him.

So famous was the Israeli millionaire in Nairobi’s Jewish circles that

his memory is etched on a stained glass window at the city’s Jewish

synagogue, donated by his family to celebrate his legacy. In

Nairobi’s Industrial Area, the family ran an engineering firm, East

African Hydraulic and Metal Industries Limited.

Read: Pastor named in Sh90m church land sale dispute

By acquiring more than 900 acres of modern-day Donholm, Tena,

Savannah, Greenfields and Tassia estates from the estate of James

Kerr Watson, the Israeli co-opted politicians out to get a slice of the

land. By doing this, he thought he was secure.

Goldberger’s Continental Developers Limited was registered in

1973, with a nominal share capital of Sh200,000. The tycoon had

listed the company’s head office as LR 209/4390 along Dar es

Salaam Road, which also housed his engineering firm.

To protect himself, Goldberger had listed President Jomo Kenyatta’s

daughter Margaret, Dr Njoroge Mungai (Kenyatta’s first cousin) and

Harun Muturi (Kenyatta’s in-law) as co-directors.

Before Githunguri threw him into financial turmoil, Goldberger

had first developed Old Donholm and had started developing

Mountain View estate. Then, he ran out of cash and decided to sell

some plots on the expansive Donholm farm.

First, Goldberger subdivided 98 acres of modern-day Tena estate

into 900 plots after Teachers of Nairobi (Tena) Sacco agreed to

purchase them for its members. In the initial arrangement,

Continental was to design the houses to maintain a look similar to

the neighbouring Buruburu. Goldberger’s dream was to have an

organised Eastlands with laid-out infrastructure.

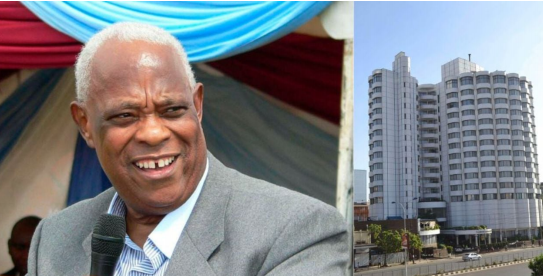

Read: Githunguri, the banker who had President’s ear

To raise money, Yoji, as Goldenberg was known in Nairobi, sold the

Old Donholm shopping centre to Ignatius Nderi, the director of the

Criminal Investigations Department. He then sold some land to a

It was during this period that Goldberger, known for his deep love

for classical music, was introduced to the man who would change

his life – the executive chairman of the National Bank of Kenya

(NBK), Githunguri, the president’s banker.

While Muturi was Continental’s managing director, the man who

ran the show was Goldberger – after all, he was the main

shareholder. So Muturi would sign the chequebook leaves and

leave them with Goldenberger.

Court records indicate that on November 19, 1976, Goldberger and

Muturi went to see Githunguri and they executed a debenture, or

rather signed a loan of Sh10 million from NBK to develop

Donholm estate houses. That was the first loan.

would give rise to the land chaos in Tassia estate, Nairobi.

As the High Court would later find out, Githunguri intended to

defraud NBK with that Tassia land.

To do that, Githunguri had organised to have Continental build

some 814 houses for Sh164 million on the Tassia land, which he

now owned.

NBK had agreed to advance Sh85 million to Goldberger’s company

while the balance would be paid on completion and after

production of the occupation certificate. Interestingly, the bank was

to purchase all the houses for its employees after completion. As

the paperwork was being done, Kenyatta died in August 1978,

throwing most of his loyalists off-balance.

Resolution

Continental’s directors then passed a resolution to borrow some

Sh85 million from NBK – some three days after Kenyatta was

buried. That resolution was signed by Goldberger and Muturi on

November 3, 1978 as the chairman and managing director,

respectively. They then took it to NBK headquarters where they

signed a personal guarantee of up to Sh85 million.

Read: Former MP and estate agent in row over Sh79m

On November 9, 1978, Goldberger and Muturi received a letter,

Ref.AKN/vmm/11/6678 from AN Ngwiri, a chief branch manager

at NBK’s Harambee Avenue branch, confirming that the

headquarters had authorised a loan of Sh80 million, “bringing the

total indebtedness to us to Sh83,032,116”.

With that letter, Goldberger was asked to execute a first legal charge

for Sh80 million over the 900 acres on LR No 212/3, which is the

In another paragraph, Goldberger was told that the whole amount

owed must be liquidated within two years from the sale proceeds of

the Donholm houses. That letter was copied to M/s Waruhiu and

Muite advocates representing the bank.

What was not being said was that the Donholm houses were on

land already owned by the bank’s executive chairman. In essence,

NBK was financing a developer to build houses on land owned by

its executive chairman and then buy back the complete houses,

ostensibly from the developer, but in essence, it was Githunguri

who would earn the profits.

During the court hearing that followed, Justice Simpson remarked

that “there was a great deal that (Githunguri) did not wish to

disclose”, perhaps the reason why the matter was heard on camera.

Sh50 million from the loan account as he promised to bank it in an

interest-earning account. They then signed what became known as

“NBK Donholm House Scheme”. Tassia, as per the records, was not

featured in the scheme. It was their secret.

Goldberger told the court that Githunguri asked him to return to

his NBK office with the company’s cheque book. He went

accompanied by a Mr Benjamin, his manager. As he told Justice

Simpson, Githunguri asked him to write two cheques for Sh15

million and Sh20 million in favour of a Ms Njeri Njoroge and

another cheque of Sh15 million in the name of Jenkinson & Parekh,

a company that had been mentioned adversely in the 1966 maize

scandal involving Cabinet Minister Paul Ngei’s wife Emma.

During the in-camera hearings, Githunguri denied giving such

instructions or offering to place the Sh50 million in an interestearning deposit account. But the court found Githunguri’s initials

on each of the cheques and wondered whether he was truthful

given that he had “evasively denied any connection with Tassia

Coffee Estate”, in which he then owned a 90 per cent stake.

Justice Simpson was at a loss: “I find it very difficult to believe that

Mr Goldberger and Mr Muturi would pay out Sh50 million to

strangers merely on a verbal promise by the executive chairman of

the bank. However, I have no doubt that Mr Githunguri did indeed

ask that the cheques be made out in the names of the two payees.”

Was NBK liable? Justice Simpson thought that Githunguri asked

for these transfers in his private capacity.

“I do not believe he was acting as executive chairman of the bank,

nor do I believe that either Mr Goldberger or Mr Muturi thought he

was so acting,” he said.

After Githunguri was removed from the bank in 1980, Muturi

decided to follow up on the Sh50 million deposit with a letter dated

February 26, 1980. He thought it would still be intact. However,

after discussions with the managing director, Mr JAC Smith, he

realised there was no such account.

Muturi realised that Continental was paying interest on a Sh50

million facility that it could not access – and NBK was deducting

the money from its current account.

Ballooned

Meanwhile, the bank started demanding that Continental repays

the loan advanced to it – including the Sh50 million. This

ballooned to Sh127 million.

“It follows that (Continental Developers) owes money to National

Bank and National Bank owes no money to Continental,” ruled

Justice Simpson.

As the NBK project collapsed, the ruins were legally on land owned

by Githunguri.

As auctioneers descended on his estate, he tried to salvage part of

the land, now Tena estate. One of former President Daniel Moi’s

sons, Raymond, had agreed to develop some 88 bungalows. But

Raymond ran short of cash and Goldberger took over the project.

rise – he started developing Lilian Towers in the early 1980s. He

found peace within Nairobi’s Freemason Lodge, while Muturi went

for the bottle. He would later find solace in building Nairobi’s

Mamba Village.

Finally, Goldberger, who never built a house for himself, left his

Sh50,000 a month rented house in Riverside for Israel.

Tena, his dream scheme, saw new developers build uncoordinated

houses. As a result, only Goldberger’s road network remained

intact, and the face of Eastlands was forever changed.