The death of Albert Ojwang while in police custody has exposed deep cracks in Kenya’s police oversight system.

Ojwang, a 31-year-old teacher and blogger, was arrested on June 6, 2025, after being accused of defaming Deputy Inspector General Eliud Lagat on X.

Just three days later, he was found dead in a cell at Nairobi’s Central Police Station. The initial police report claimed he had banged his head against the wall, but a postmortem revealed clear signs of assault. His body showed injuries that could not be self-inflicted, including deep bruises on the head and limbs. This sparked national outrage, with people demanding justice and accountability, especially from the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), which took over the investigation.

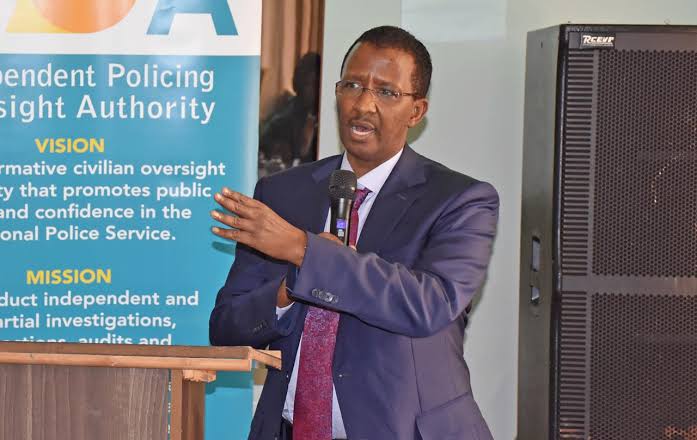

According to the report on X by NTV, IPOA interviewed Eliud Lagat in secret, away from the media, which has raised serious questions about transparency.

Many now feel IPOA is shielding powerful individuals. The fact that Lagat, the very person who filed the complaint leading to Ojwang’s arrest, is being investigated by an institution that kept his statement confidential has only made things worse.

Public trust in IPOA is quickly eroding, and people are beginning to ask whether the authority can truly hold top police officers accountable.

IPOA has arrested three people so far: Constable James Mukhwana, who was the cell sentry; Officer Commanding Station Samson Talam; and CCTV technician Kelvin Mutisya. Mutisya allegedly received $30 to disconnect the CCTV system, which shows a clear effort to cover up what happened. Talam is said to have been in direct contact with Lagat and even paid inmates to beat Ojwang.

These details came from witness statements and CCTV footage that IPOA was able to retrieve. Yet despite this disturbing evidence, IPOA has only targeted low-level officers. The public wants to know why no action has been taken against Lagat, who clearly played a central role in this incident.

Critics, including Rarieda MP Otiende Amollo, have accused IPOA of running a half-baked investigation. He pointed to many gaps and urged Parliament to step in. There are also concerns that IPOA Chairperson Issack Hassan’s past dealings with Lagat might be influencing the investigation.

This conflict of interest is alarming. While IPOA has been quick to parade constables and technicians, it is dragging its feet when it comes to senior officers. People see this as selective justice, and many are convinced that the delay in charging Lagat is deliberate.

The public mood is sour. Many believe that unless Lagat is arrested or suspended, the whole investigation will be meaningless. The Directorate of Public Prosecutions had given IPOA a seven-day deadline to complete investigations, which ended on June 20.

But with no additional arrests, Kenyans are left with more questions than answers. If IPOA truly had nothing to hide, then why was Lagat’s questioning done in secret? And if the evidence points to him ordering or influencing Ojwang’s beating, why is he still free?

This case has shown how fragile Kenya’s police accountability system is. IPOA may have started with arrests, but its unwillingness to touch high-ranking officers has destroyed its credibility.

As things stand, it looks like IPOA is more interested in protecting careers than protecting citizens. If Lagat is not held accountable, then the message is clear powerful police officers can kill with impunity.